Decodable books: A comprehensive guide for educators and parents

Decoding is a foundational skill in learning to read. Literacy expert and author Lousia Moats defines “decoding” in her influential book Speech to Print as: “[the] ability to translate a word from print to speech, usually by employing knowledge of sound-symbol correspondences; also, the act of deciphering a new word by sounding it out.”

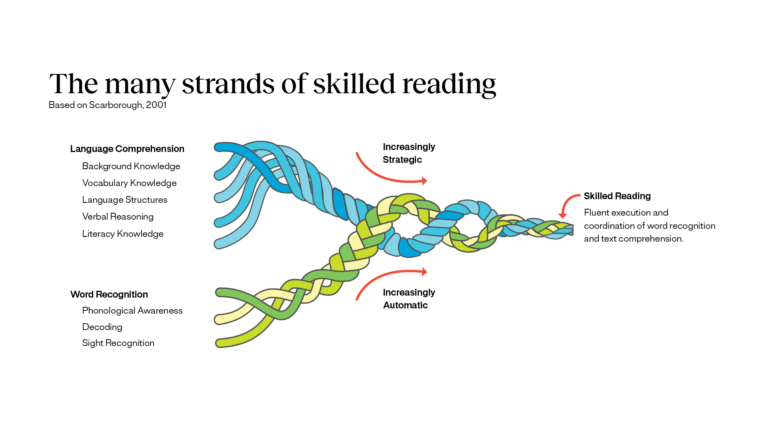

In the well known Scarborough’s Reading Rope, a visual metaphor for skilled reading, decoding is one of the three strands of Word Recognition (phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition), that when combined with the five strands of Language Comprehension (background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, literacy knowledge), leads to skilled reading.

Research has shown that systematic and explicit instruction play a critical role in students learning to decode effectively.

What are decodable books?

“Purposefully designed text.” That’s how Laura Stewart, Chief Academic Officer of 95 Percent Group, describes decodable books. Purposely designed for what? Ideally, decodables provide text that is aligned with what students have been taught already to let them practice their decoding skills, to build confidence, automaticity, and fluency with known patterns and words. With decodable text, students can apply the phonics skills they are learning as they are learning them.

Stewart offers this definition from a paper by Castles, Rastle, and Nation: “Decodable books are texts written for children that consist primarily of words they can read correctly using the grapheme-phoneme correspondences that they have learned (with the exception of a few unavoidable irregular words).” She adds: “Decodable texts allow our students to apply the fine skills that they’re learning as they’re learning them. It allows them to develop the decoding habit that will lead to accuracy, fluency, and mastery, building young readers’ confidence.”

Decodables are intended to support beginning readers, although in specific cases, they might be used with older students as well. As researcher Heidi Mesmer explains, they are like training wheels while students are building the neural connections required for automaticity and fluency. The main purpose is to reinforce phonics skills, improving a student’s ability to decode words independently.

What are leveled readers and how do they compare with decodables?

Leveled reader systems have been used in education for many years to support students with gradual skill improvement using reading content organized based on complexity and age-appropriate content. The goal of leveled texts is to match readers with books that are at their current reading level, allowing them to read with some fluency and comprehension without being so challenging that they become frustrated.

Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell played a major role in the development and popularization of leveled readers in the mid-1990s with the introduction of their Guided Reading Model and Leveled Literacy Intervention (LLI). Various leveling systems—Fountas & Pinnell, Lexile Framework for Reading, the Accelerated Reader, vary widely in how they rank students. Some systems, such as Fountas & Pinnell’s LLI, have been criticized for being difficult for teachers to detect error patterns because students can use compensatory skills such as guessing at words based on illustrations provided. According to reading researcher Timothy Shanahan, the determination of levels has never been validated by rigorous research.

Nina A. Lorimer-Easley, MS, MEd, associate director for education and outreach for the Iowa Reading Research Center, offers this critique of the leveled readers:

“Readability levels are determined by measuring word frequency and sentence length, rather than the scope and sequence of decoding instruction. Leveled readers also are typically brightly and ornately illustrated, giving students images and ample context to guess what the words are in the text. This can make it very difficult for educators to detect error patterns because students can use these compensatory skills to read. Moreover, there is no consistency in the skills required to read a given text. Together, these characteristics can make it difficult to know from children’s performances with the leveled readers what adjustments, if any, should be made to foundational skills instruction.”

A common concern is that leveled texts, especially those at lower levels, may not provide enough phonetic challenge to support the development of decoding skills. According to literacy expert Louisa Moats, a leveled reader “doesn’t form that all important decoding habit that we know is critical in forming those neural pathways for securing the alphabetic code, enhancing orthographic mapping for automaticity of word retrieval. And, in fact, frankly, what we know now is that using text like this encourages kids to adopt the habits of what poor readers tend to do as opposed to solid, fluent readers.”

Let’s compare key features of decodables and leveled readers.

| Decodable books: | Leveled readers: |

| – identify and teach new vocabulary up front in advance of students reading | – determine “levels” by word frequency, sentence length |

| – present words and word structures in scope and sequence of skills in curriculum, or by patterns of vowels and consonants introduced (e.g. VC, CVC, CV, etc.) | – match student reading ability, age, or grade |

| – use few illustrations to discourage guessing/inferring word meanings | – typically provide illustrations as context to help students guess/infer the words |

| – build the neural networks required for reading | – build visual forms in right hemisphere of brain which doesn’t lead to skilled reading |

| – intended for use in early stages of reading | – used across various stages of reading development |

What is the relationship of sight words to decodables?

Let’s define sight words. Sight words are typically but mistakenly thought of as high-frequency words such as “the,” “of,” “and.” They include a subset of words that diverge from standard patterns.

Louisa Moats corrects a common misperception about “sight words” in her book Speech to Print. She writes: Sight words are “known words that are recognized instantly and do not have to be sounded out or consciously decoded; [the term “sight words”] is often confused with the mistaken idea that high-frequency or somewhat irregular words must be taught by rote memorization as ‘outlaw,’ or ‘nonphonetic,’ words.” In fact, the goal is that all words can be stored in our mental lexicon to be recognized automatically, as if “by sight.”

As we learn words through phonetic decoding and practice those words with decodable text, we are facilitating that repetition that is required for the orthographic mapping of words into our mental lexicon so they can become “sight words.”

With that being said, there certainly are words that are irregular and don’t follow a typical decodable pattern. But in teaching those words, teachers can still help students identify any decodable parts of the word, then point out the irregular patterns or phonetic elements in those words (that irregular part is often signified by placing a “heart” over it to help a student signal that this part of the word cannot be sounded out; hence these high-frequency irregular words are often called “heart words”) to help secure that word for the student. Only a very few words are so irregular that they must be taught by memorization.

Because high-frequency, non-decodable, irregular words are often needed to make sentences that are meaningful, decodable books include them as needed for sense making but limit the number used to prevent students from needing to guess at words. When presenting a new decodable to students, teachers typically teach up front any of the irregular words that are included.

Why use decodable books?

Decodables play an important role in building students’ confidence and fluency. In the webinar The Power of Decodables in Learning to Read, (see link below), Laura Stewart discussed research on motivation by Adam Grant in his book Hidden Potential. She shared with webinar viewers:

[Grant] “emphasizes that the research is really clear that the greatest factor in motivation is progress. Decodable text allows children to know that they are progressing as real readers. Grant writes (on page 123): ‘Of all the factors that have been studied, the strongest known force in daily motivation is a sense of progress.’”

Stewart sums up the research on decodables with the keywords decoding strategy and accuracy plus these three points:

- The kind of text we put in front of beginning readers determines the strategies that they will use.

- First graders who were learning phonics and using highly decodable text were more likely to employ their letter-sound knowledge than those using less decodable text.

- These students tended to read more words accurately and need less help getting through a text.

For a more in-depth analysis of the research, you can read a summary of the conversation with Laura Stewart and Joni Maville, 95 Percent Group’s director of content development, here. You’ll also find a link to watch this excellent, on-demand webinar.

Common concerns

Decodable books have been critiqued for not being real literature. It’s important to understand that decodables are not meant to be real literature. The classroom should be rich with literature for read-alouds and shared reading, to build vocabulary, knowledge of the world, and comprehension. Decodables serve a different purpose—to teach decoding skills explicitly and systematically, and to provide an opportunity to apply those decoding skills using cumulative, decodable text to build the critical neural connections for automaticity and fluency.

Decodables have also been criticized for limited vocabulary but research (Dixon, 2016) has shown that decodables have a richer vocabulary than leveled text. Simplicity in the beginning is intentional and should be carefully aligned with phonics instruction scope and sequence. The text in decodables is designed to become more complex as students progress.

Choosing the right books

Decodables should not be considered as standalone resources. Ideally, they are a critical part of a literacy ecosystem that includes core phonics instruction, assessments and screeners, intervention support, and embedded teacher professional development. When choosing decodables, look for books aligned with best practices in the science of reading and aligned with the scope and sequence of an evidence-based phonics core program. Within the context of a core phonics program and robust literacy ecosystem, teachers will gain the support they need to use decodables effectively.

For more input selecting high-quality, decodable text, read the post, The power of decodables in learning to read. You’ll find a list of features to ensure you choose high-quality decodables, as well as some examples of innovative K-1 decodable texts with a unique flip format.

Beyond decodable books

Once students’ foundational decoding skills are strong, students can progress to engage with more complex texts. The goal at this new stage becomes consolidation of skills in the service of accurate and fluent reading for meaning (Moats, 2020). Example teaching activities would include teacher guided, small-group shared reading of high quality texts as well as partner reading and book groups, with a goal for students of independent reading and monitoring of comprehension.

Ideally, students are reading decodables and progressing to more complex texts within a robust literacy ecosystem with common language and routines and consistent instructional strategies across the grades and tiers. This approach supports accelerated literacy improvement for all children.

The final word

High-quality, evidence-based and evidence-aligned decodable books support early readers in becoming confident, strong, and fluent readers. The decodables create a bridge between learning phonics and applying phonics in independent reading of text (Moats, 2020). Experiencing early and ongoing success in reading helps support students on their learning journey throughout their lives.

Of all the factors that have been studied, the strongest known force in daily motivation is a sense of progress.

Adam Grant

Additional resources

On-demand webinar, The Power of Decodables in Learning to Read.

95 Decodable Duos™, an innovative new book series—developed to align with best practices in the science of reading and the scope and sequence of 95 Phonics Core Program®.

For more information on any of 95 Percent Group literacy resources, including the new 95 Decodable Duos series, contact us today!

Sources

Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the Reading Wars: Reading Acquisition From Novice to Expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 5-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618772271

Cheatham, J.P., Allor, J.H. (2012) The influence of decodability in early reading text on reading achievement: a review of the evidence. Reading and Writing, 25, 2223–2246 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-011-9355-2

Dixon, B. (2016). What happened to the ‘D’ word? LDA Bulletin, Volume 48, No. 3, 28-29. Spring 2016.

Lorimor-Easley, N. A. “The Role of Decodable Readers in Phonics Instruction.” Iowa Reading Research Center blog, (2020). https://irrc.education.uiowa.edu/blog/2020/11/role-decodable-readers-phonics-instruction

Mesmer, H. A. E. (2005). Text Decodability and the First-grade Reader. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 21(1), 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560590523667

Moats, L. C. (2020). Speech to print: Language essentials for teachers (3rd ed.). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Pondiscio, R. (2019). Leveled Reading: The Making of a Literacy Myth. Education Next, 19(4). Retrieved from https://www.educationnext.org/leveled-reading-making-literacy-myth/

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. Neuman and D. Dickinson (Eds.) Handbook for research in early literacy, (pp. 97-110). Guilford.

Shanahan, T. (2022). Rejecting Instructional Level Theory. Retrieved from blog (4.25.2024). From https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/rejecting-instructional-level-theory