Courageous leaders: The power of conviction, with Laura Stewart and Louisa Moats (part 2)

Laura Stewart, Chief Academic Officer at 95 Percent Group, spoke with author, speaker, and literacy advocate Louisa Moats, EdD, recently in the Courageous Leaders Webinar Series. In Part 2 of their conversation, they explore leadership and literacy in more depth.

Laura Stewart:

Let’s begin Part 2 of this Courageous Leaders interview with Louisa Moats reviewing some of the words she used in Part 1 in speaking about leadership:

- Have relentless conviction that you’re doing the right thing

- Name and actualize a vision

- Find the courage to lead toward it

She suggested asking yourself continual questions:

- Am I teaching the right stuff?

- Is it necessary?

We have to keep asking ourselves the right questions so that we can continue to examine and improve our practice. It’s not someplace that we’ll ever have arrived.

Let’s pick up the conversation there, Louisa.

Louisa Moats:

We can’t ever become complacent. There’s always more to learn, and I think that’s part of the reason I’m here talking to you and still doing these things that I’m doing—there’s always more to learn. And for me personally, it’s always exciting to learn something new, or to have a different insight, or to observe the work in progress and the results that come with it. It’s always rewarding.

Laura Stewart:

I do think that we’re fortunate in that we’re in a profession that is very dynamic. I think it’s a real privilege to work in a profession in which we can be continual learners, and that will benefit our students.

The power of collaboration

Laura Stewart:

Back to our leadership focus—so courageous, relentless conviction, asking questions, be patient, stay the course. This literacy work that we’re doing takes a long time. Are there any other words of wisdom that you could impart to district leaders or building leaders, or even teacher leaders to help them lead this transformative change in their schools and districts?

Louisa Moats:

I think being really open to, and not just open to, but enjoying collaborating with other people whom you respect. It’s so important to embrace the talents of other people, and know when you have limitations. Find people who compliment you, and who approach the whole enterprise with the same attitude—mutual enrichment and collaboration. Some of my most wonderful long term relationships have been with collaborators.

Laura Stewart:

Yes, this work is meant to be collaborative problem solving. I’ve heard my good friend Terry Nolan say things about how leadership is not positional. Right? So it isn’t that you’re a leader that has to solve this problem. You work with others in the collaborative problem solving model.

Louisa Moats:

Yes, this makes me think about Susan Hall, who started 95 Percent Group. Susan and I wrote a book in 1999 called Straight Talk about Reading. I think you could still find it on the Internet. She was really interested in reading, and she had a background at Harvard Business School. She approached me and said, “I need some expertise. I want to write a book.” So we teamed up and we wrote several books, and then she developed the company. That was a fun collaboration, just learning from her how she thinks about business totally different to me, and how organized her mind is, and what questions she asked—I would never have thought of that.

Laura Stewart:

Yes, so that was a good collaboration, because you brought your different strengths and weaknesses together. Susan Hall was one of our guests on the Courageous Leaders series. The recording of this conversation is available on demand here.

Literacy—what we’ve gotten right and what we still need to do

Laura Stewart:

Let’s talk a little bit about literacy. What do you think we’ve gotten right? In what areas are we moving forward in the right direction? And in what areas do you think we still have a long way to go?

Louisa Moats:

Great question, Laura. I think what we’re getting right now is the importance of teaching foundational reading skills. And there are some really good tools for people to use that are out there and available now that are real improvements on what has been out there before.

However, the muted warning from a lot of different corners in our field about over-emphasis on decoding, to the exclusion of some other things, is to be taken seriously. First of all, spelling is not being taught, or not being taught well—it’s very important, and really needs to get its due in the course of a foundational skills lesson. It needs to be informed by research. And we need to be using assessments to figure out where kids are in their spelling development, in relation to their reading development, and teaching that. We’ll come back to that.

But the other thing, in addition to writing, is language—language development, language comprehension. What concerns me as I look at the internet chats, and also the policies that states are writing about the 5 components of reading is this—teachers, unless they have better education, are thinking “There must be a book on teaching reading comprehension that I can get my hands on to do that component.”

But no, that’s not what this is about. It’s about nurturing language development, doing it systematically and explicitly, using tools like Language! for literacy learning, which is one of the oldest and best things out there. Direct instruction. And what is the vocabulary you need in kindergarten to follow what the teacher is saying and do what you’re being asked to do?

We need to look at language development and the opportunities all through the day for everything that goes on in school to develop language very consciously in kids who are lacking good language skills, and that’s most of them. So that’s my concern. I want us to get to the point where there’s enough security and stability in our classroom instruction of basic reading and spelling skills that then this other other half of the simple view, the other strands of the reading rope, are going to be addressed with much wiser approaches.

Literacy is all about language

Laura Stewart:

Do you think there’s any validity to the noise around the idea that the science of reading is all about phonics or all about foundational skills?

Louisa Moats:

Only if we allow it to be. It’s not what the science is about at all. There’s lots of science about vocabulary learning, about early language and its relationship to literacy. All the work of Snowling and Hulme from Great Britain, and the whole thesis with reams of research is literacy is all about language. It predicts everything, and intervention needs to start early, and this is how you do it.

Again, I’m back to teachers who understand the content of language and the process of gaining facility with language and the relationship between oral language and written language, and how you nurture that in the classroom. So the teachers have to be encouraged and given models over and over and given tools. Think of what they have to let go of…The classroom should be quiet. No. Wait till a kid raises a hand before he talks. No. That concept of a traditional classroom being quiet, orderly, with handraising going on. All that needs to go. There’s lots of research about all of this. It’s just not getting as much air time, because the shift to teaching foundational skills has taken so much effort and so much bandwidth and so much education and time.

Laura Stewart:

Yes. We, as an educational community, had to put time and effort into that because that was a missing link. People didn’t know what you talk about in Speech to Print. People didn’t have this knowledge base. So we had to put time and effort into that.

Summarizing what you just said—spelling obviously, we need to head in the right direction there. Language development, systematic language development, even understanding that oral language can be facilitated throughout the day, raising our consciousness about how our classrooms sound and look so the kids are developing that language piece, and you mentioned you think our kids are needier in this more than ever. Can you comment a little bit more about that?

Louisa Moats:

Well, they are. I mean, our technology is not doing us any good when it comes to kids learning to express themselves in a persuasive way, or even in an acceptable way. Not everybody’s going to be writing books, but kids need to be able to write a coherent memo or email message, or express their opinion about something, and need to be able to engage in verbal exchanges that are more than text language. It concerns me greatly.

And when I look at our national test scores in relation to where technology has brought us for the last, let’s say, 20 or 30 years, there has not been a great improvement in national verbal ability. The emphasis on telling everything with pictures has real limitations. I worry, because in a civil society, this gets back to our democracy surviving—it will only survive if people are in conversation with each other about important matters that affect everyone. You can’t do that unless you’re armed with some skills of self expression and discourse.

Laura Stewart:

I think back to what Maryanne Wolf always says about the importance of developing those deep neural capacities for reading complex text that allow us to develop empathic connections to the other. And we are at risk as a society if we don’t develop those empathic connections through reading, through civil discourse. These are things that we have to attend to. So thank you for naming them.

Are policies helping or harming?

Laura Stewart:

You mentioned policy. How important do you think policies are in moving the needle?

Louisa Moats:

You know I’ve seen it all at this point. Policies can sometimes get in the way if they’re too directive, too explicit, or if they have a punitive aspect to them. What I’ve seen work the best is leading people by explaining to them and showing them with evidence, arguments, and information about what is going to work better. I think a lot of the policies that we have now are the result of parents really forcing state legislatures to do something about the fact that their kids weren’t taught how to read. And in the interest of doing something, some of the policies are overly prescriptive. So we’re stuck.

Here’s an example. All of them name 5 components that came from the National Reading Panel. Well, in reality, good instruction is not broken into 5 components. Good instruction is integrated so that it flows through these components. It addresses them. But there’s coherence and meaning and flow in the lesson. So you don’t have a book for phoneme awareness, a book for phonics. We don’t want that, but policies can be misinterpreted. So policies need to be implemented by people who have a lot of good guidance and information.

So I’m very ambivalent about policies, unless you have a whole state, as with Mississippi, “the Mississippi wonder,” that happened, because the entire state and everybody involved in that initiative was on the same page, working with the same vocabulary, doing the same stuff for the same purpose, with the same goals in mind, and that was really unusual.

Laura Stewart:

Yes, we need to have the right people in the boat and all rowing in the same direction. I think about what Kymyona Burk says—that people talk about the “Mississippi miracle.” She’s clear: “It was no miracle. It was a lot of work.” And I think that’s the other lesson for leaders, too. The hard work doesn’t end. It is relentless. You can’t take your foot off the gas and go, “We’ve done it.” It’s just relentless work.

Louisa Moats:

And if you take your foot off the gas, things will drift back to whatever is intuitive or easier, whatever.

Laura Stewart:

But it’s work that we get to do.

Louisa Moats:

Work we get to do. That’s lovely.

Hopes and dreams for teachers and kids

Laura Stewart:

Please tell us as we wrap up here, what are some of the hopes and dreams you have for teachers and kids, Louisa?

Louisa Moats:

Well, I just hope first of all, if our society ever got to the point of really honoring the teaching profession, that would be wonderful. I’ve seen that in other countries like New Zealand, visiting there and seeing how teachers were educated and treated and supported and paid, and their working conditions.

But it’s so different in other countries. Why can’t we as a society recognize how critical our teachers are, pay them accordingly, improve their working conditions, stop layering every social ill and responsibility for everything under the sun onto our teachers and focus on teaching because it is complex and challenging, as challenging as any other profession.

I don’t know what it will take, but that’s what I hope.

And then I hope that our teacher education programs continue to take all this seriously and improve. I’m very heartened by the work that’s going on with the consortium in the Path Forward initiative—these are all really good things. But there’s a lot of work to be done there to ensure that teachers come out with their license with the right mindset, and then they’re going to still learn.

Another thing I wish is that a novice teacher was never thrown into a classroom and told to sink or swim, and that’s still going on. Everybody needs mentors. Everybody needs examples, supports.

The meaning of conviction

Laura Stewart:

I have one last question for you, Louisa. We called this webinar the power of conviction. Could you close by sharing what this word means to you, and how conviction has played such a strong role in your life.

Louisa Moats:

Conviction means that you just have this visceral sense of a truth or set of truths, the goal to pursue those truths and live by them. That’s what it means to me.

Laura Stewart:

I love that visceral sense of truth that you live by. Thank you for this—such immense wisdom and honesty and vulnerability about what you’ve been through, and so many lessons learned.

Did you miss part 1?

Click here to read now!

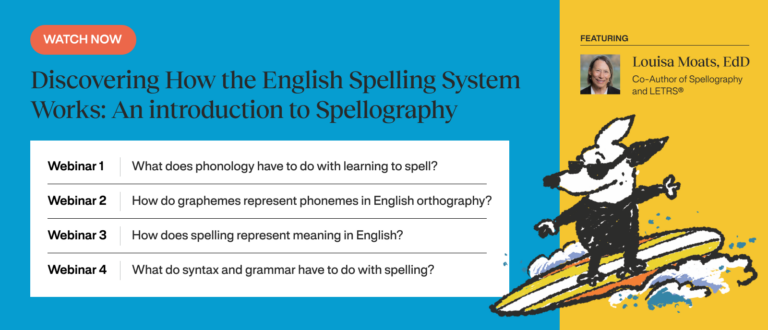

Learn more with Dr. Louisa Moats

In this four-part webinar series, “Discovering How the English Spelling System Works: An introduction to Spellography”, taught by Dr. Louisa Moats, co-author of Spellography, we will break down the layers of language and help educators see how the various parts work interchangeably together and build upon each other. Spellography is a classroom-tested program that explicitly teaches spelling concepts to help students make sense of the English spelling system and become better at understanding, reading, and writing words.

About 95 Percent Group

95 Percent Group is an education company whose mission is to build on science to empower teachers—supplying the knowledge, resources and support they need—to develop strong readers. Using an approach that is based in structured literacy, the company’s One95™ Literacy Ecosystem™ integrates professional learning and evidence-based literacy products into one cohesive system that supports consistent instructional routines across tiers and is proven and trusted to help students close skill gaps and read fluently. 95 Percent Group is also committed to advancing research, best practices, and thought leadership on the science of reading more broadly.

For additional information on 95 Percent Group, visit: https://www.95percentgroup.com.