Orthographic mapping: The key to building strong readers

A post from our Literacy Learning: Science of reading blog series written by teachers, for teachers, this series provides educators with the knowledge and best practices needed to sharpen their skills and bring effective science of reading-informed strategies to the classroom.

Have you ever wondered why some students seem to read a word once and recognize it forever—while others appear to “learn” a word but forget it the next day? The answer is almost always the same: orthographic mapping.

Orthographic mapping is the brain-based process that allows readers to store words permanently in long-term memory for instant retrieval. It’s truly the foundation of fluent, accurate reading. Without it, students struggle to move beyond sounding out every word on the page.

So what is orthographic mapping, how does it work, and how can educators support it?

Let’s break it down.

What is orthographic mapping?

When readers apply their grapheme–phoneme knowledge to decode new words, connections are formed between graphemes in written words and phonemes in spoken words.

This bonds the spellings of those words to their pronunciations and meanings and stores all of these identities together as lexical units in memory.

Subsequently, when these words are seen, readers can read the words as single units from memory automatically by sight (Sargiani, R.D.A., Ehri, L.C., & Maluf, M.R., 2021).

Orthographic mapping is a mental process—not a teaching strategy—where the brain maps (or permanently bonds) the sounds in a spoken word to the graphemes that represent those sounds in print. When this mapping process happens successfully, a word is stored for automatic retrieval. We have previously been taught that when kids are learning how to read ‘sight words’ they are memorizing them—by sight. But the truth is that this is orthographic mapping in action.

It’s how a child moves from slowly decoding /k/-/a/-/t/ to instantly reading “cat”, “went”, or even more complex words.

Word recognition is essentially having words stored permanently in your long-term memory—it’s your ability to read words efficiently, accurately, and effectively. That’s the ultimate goal we have for all of our students.

Dian Prestwich

People frequently mistake orthographic mapping for something you teach, but it’s actually a process—something the brain does—when the reading instruction provides the right ingredients:

- The development of strong phonemic awareness

- Phonics instruction that results in decoding/word recognition accuracy and automaticity

- Lots of practice in text, beginning with text that provides practice in learned phonetic elements (instruction-based decodable text)

The research is clear—and all fits together to show that the brain becomes skilled at reading by processing every letter and sound, not by memorizing whole shapes or ‘guessing’ from context. A few core theories help explain why.

1. Ehri’s phases of reading development

Linnea Ehri, a member of the Reading Hall of Fame and the National Reading Panel, has been researching how children learn to read and write since 1970. Her ‘phases of reading development’ framework helps us to understand why we need to explicitly teach children to pay attention to each sound in a word instead of trying to look at it as a “whole.”

Students move from:

- Pre-alphabetic phase: little phonemic awareness, letters aren’t linked to sounds

- Partial alphabetic phase: children pay attention to the first letter and then might guess

- Full alphabetic phase: blending, segmenting, and letter-sound knowledge allow true mapping

- Consolidated phase: students store and recognize familiar spelling patterns

- Automatic phase: students decode words effortlessly, freeing cognitive capacity for comprehension

Linnea Ehri coined the phrase “orthographic mapping” in 2014.

2. Perfetti’s dimensions of word knowledge

According to Charles Perfetti’s concept of word knowledge, the more you know about a word (its sounds, letters, meaning, and morphology) the faster your brain will be able to retrieve it. This means that orthographic mapping plays a very important role in foundational decoding work for children learning to read.

Mapping phonemes and graphemes (letter sounds and names) to meaning and understanding multiple word meanings—essentially knowing more dimensions of a word—improves retrieval from long-term memory for reading and spelling. Even with irregular words like ‘said,’ teaching them in context enhances word retrieval capabilities.

Dian Prestwich

3. Stanislas Dehaene’s neuroscience of reading

Dehaene’s work helps explain how four different parts of the brain work together to process language in learning to read:

- The visual cortex: in the Occipito-temporal region that helps us perceive letters and words (sometime called the “letterbox”)

- The phonological cortex: in the Temporoparietal region that maps the sounds to letters

- The semantic cortex: in the Inferior frontal gyrus Temporal lobe that stores word meanings,

- The syntactic cortex: helps us understand the rules and structure of sentences

Words that are stored across these systems become ‘permanent’ and thus easier to quickly retrieve from long-term memory for reading and spelling. While this process ‘looks like’ knowing words by heart, this is actually a function of orthographic mapping.

4. Seidenberg and McClelland’s four-part processor

Seidenberg and McClelland provided a cognitive framework that explains how skilled readers recognize words quickly and accurately, forming a cornerstone for current reading instruction and research. Their four part processing system shows that in order to store a word, readers must activate:

- Phonological processors

- Orthographic processors

- Meaning processors

- Context processors

That means orthographic mapping happens when we offer students explicit instruction in multiple areas:

- Phonemic awareness (identifying the smallest units of sound in words)

- Phonics and spelling patterns

- Vocabulary and morphological awareness (identifying the smallest units of meaning in words)

- Syntax (correct grammatical use of words in language)

These are all important concepts involved in a structured literacy approach based in the science of reading.

How orthographic mapping develops in children

So what specifically do we need to help children understand or develop in order for the orthographic mapping process to take place?

- Strong phonemic awareness (especially blending & segmenting): The ability to identify and manipulate sounds within a word is one of the strongest indicators of reading success

- The alphabetic principle: the understanding that sounds (phonemes) are represented by written letters or patterns (graphemes) is essential to reaching automaticity

- Automatic letter-sound knowledge: When these associations become automatic, the cognitive load of decoding is lifted. This allows children to expend more mental energy on understanding what they read.

- Systematic phonics instruction: Consistent, sequential and systematic phonics instruction is a critical part of the rising tide that lifts all learners.

- Repeated exposure to orthographic patterns in text: Offering children frequent opportunities to practice with text that they can access–which initially is controlled, or decodable text– is one of the most important ways to practice reading at the phrase and sentence level early in the decoding process. When students encounter mapped patterns repeatedly in controlled text, storage strengthens.

- Accuracy in word recognition: Accuracy and automaticity are critical features of orthographic mapping.

Sound-by-sound decoding and blending come first—but the goal is storing words for immediate retrieval.

What disrupts orthographic mapping?

Now that we’ve established how we can help to foster orthographic mapping in young learners, let’s look at some of the things that can disrupt or delay this process.

- Weak phonemic awareness: If students are having a hard time identifying the sounds within words, their orthographic mapping process will be disrupted. There are many strategies that can help teachers and activities that parents can do at home to help children strengthen these skills.

- Poor letter-name or letter-sound knowledge: When children have a hard time identifying letter names and sounds, it makes orthographic mapping (which relies on these) slow and difficult.

- Guessing words based on first letter or picture: Any strategies that involve guessing what a word is instead of using the sounds inside the word to sound it out, will be disruptive to the process of orthographic mapping. 95 Decodable Duo books, part of the 95 Tier 1 Phonics Solution, were created with two sides for this reason—one side without images so students can focus on the letters and sounds to decode words, and the other side with images so they can read it for a second time while enjoying the pictures.

- Lack of systematic phonics: Spelling patterns need to be taught in a systematic, cumulative nature. When we teach new patterns, students should have multiple opportunities to engage with the phonics patterns orally and in writing, with both isolated word reading and spelling practice as well as in context with text–initially controlled text—helping the information to be mapped in our students’ brains.

- Lack of sufficient practice: Students need plenty of practice in text to secure the bonds of the spelling, pronunciation and meaning of the word.

Also, teachers should begin with the simple phonics patterns and keep adding more sophisticated ones—while continually looping back to review what has already been taught. If phonics is not taught this way, if spelling patterns are taught randomly, and never practiced in writing or never reviewed, the chances of orthographic mapping occurring are much less.

Here’s what you need to know:

Research shows that skilled readers process every letter— even when reading silently. We don’t recognize whole shapes; we decode rapidly because stored orthographic knowledge is doing the work.

Supporting orthographic mapping in students

Orthographic mapping develops when instruction consistently connects:

Sounds → to letters → to meaning → to repeated use and practice

Here are some effective instructional tools for this work:

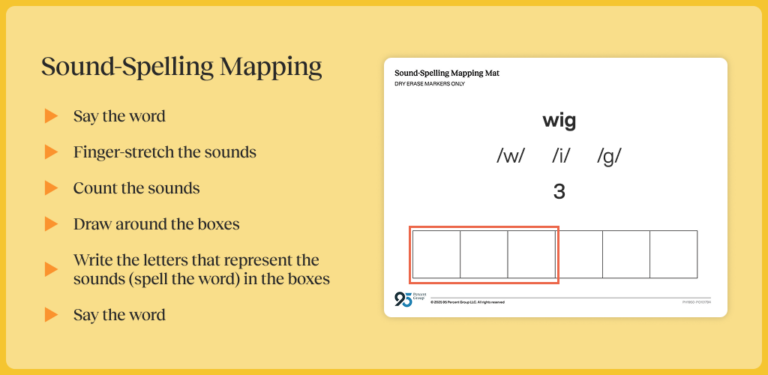

Sound-spelling mapping

Sound-Spelling Mapping is a tool that uses chips or boxes to help children segment words into phonemes. It’s similar to Elkonin Boxes, pioneered by D.B. Elkonin, a Russian psychologist. Students count sounds in each word first and move a chip into each box to represent each sound. For example, ask the student to put a chip for each sound in the word “wig.” This activity will help them visually break down the sounds of the word to /w/ /ǐ/ /g/.

Then they replace each chip (representing a phoneme) with the letter(s) or grapheme that represents the sound in the box—building a bridge from the way we say something to the way we write—and eventually—read the word.

A great example of how children map a phonetically “irregular” word is when they move through this process with a word like “said.” When a child maps the graphemes “ai” to the sound /ě/, they are developing the neural pathway in the brain that will allow the word to be saved in long-term memory.

This is orthographic mapping.

Word chaining

Changing one phoneme at a time draws attention to what sound is shifting and what grapheme represents that sound. Students can do this by changing one sound at a time to create different words.

Example: Start with the word “cat.”

Change the /k/ to /b/ → now you have “bat”

Change the /b/ to /h/ → now you have “hat”

Change the /t/ to /m/ → now you have “ham”

This activity strengthens phonemic awareness, phonics, and spelling by having students manipulate sounds and apply them to reading (decoding) and writing (encoding).

Common challenges

Not everyone’s brain has an easy time with this process. Some students may struggle to develop strong orthographic mapping when they have:

- Phonological processing deficits—This is commonly an issue for individuals that have language impairments associated with reading and often means they have poor auditory sensitivity to speech-relevant acoustic properties.

- Working memory weaknesses—If children have a hard time holding things in their short term memory, it is difficult for concepts or skills to make it to their long term memory which orthographic mapping requires.

- Difficulty with phoneme-grapheme correspondence and/or difficulty identifying separate sounds in a word– These are common challenges for individuals diagnosed with dyslexia.

- Limited early exposure to letters and sounds—

While some of these are easier than others to remedy, if you suspect a student needs extra support, it’s critical to ensure they are assessed so that they can get the instruction they need immediately.

Assessing orthographic skills

Although orthographic mapping is a process that happens in the brain, there are still things we can do to help measure whether this process is happening successfully for students.

For example, educators can look for:

- Automatic recognition of previously learned words → When a child has learned a spelling pattern and has practiced writing that spelling pattern, they should be able to recognize and decode it with more ease.

- Accurate decoding of new words with familiar patterns → Similarly, if a student sees a new word that has a pattern they have already learned e.g., “make” and “lake” which both have the /ā/ sound and the a_e spelling pattern), they should be able to accurately decode the second word after successfully learning the first.

- Transfer from word reading → reading connected text: Once students are successfully reading on the word level, they should be able to read connected, accessible text on the sentence level if it has spelling patterns they’ve already practiced.

Tools that can help assess whether students are successfully mapping:

Tools and resources to enhance orthographic mapping

Orthographic mapping is a process that can develop and become stronger through literacy instruction that is:

- Systematic

- Explicit

- Cumulative

- Supported with decodable text

How 95 Percent Group solutions supports orthographic mapping across tiers

- 95 Tier 1 Phonics Solution

- Phonics Core Program® + Sortegories by 95 Percent Group™

- 95 Tier 2 Phonics Solution

- Diagnostic screeners for phonemic awareness and phonics

- Phonics Lesson Library™ 2.0

- Phonics Chip Kit™: offers hands-on mapping when a student struggles to connect a sound-spelling pattern

- Plus many more resources!

- Tier 3 Literacy Solution

- 95 RAP™ (Reading Achievement Program)

Orthographic mapping wires the brain for fluent reading

Orthographic mapping is the key to fluent, confident reading. It’s not guesswork, memorization, or visual recognition—it’s the brain wiring sounds to print so words become permanently stored and easily retrieved again and again.

With strong phonemic awareness, structured phonics, sound-spelling mapping, and controlled text practice, every student can build a stronger orthographic mapping process—ultimately moving them towards fluent and joyful reading.

Expert Biography

Dian Prestwich, PhD

Dr. Dian Prestwich is currently a literacy consultant for 95 Percent Group, providing professional development and coaching to educators and administrators to improve student literacy outcomes. With nearly three decades in education since 1995, her experience includes 7 years as Associate Teaching Professor at University of Kansas, 6 years as Assistant Director for the Office of Literacy at Colorado Department of Education, 9 years teaching primary grades, and 5 years as an instructional coach. She has 7 years of experience as a national LETRS trainer.

Dr. Dian Prestwich serves as contributing faculty for Walden University’s Richard W. Riley College of Education & Leadership and sits on the International Dyslexia Association Accreditation Review Committee. In 2023, she served on Praxis Early Childhood Development committees. She holds a BA in Elementary Education from Northwestern State University, MEd in Curriculum and Instruction from Lesley University, and PhD from Walden University (2012). Her dissertation focused on measuring preschool teachers’ competency in oral language development.

Sources:

- Dehaene, Stanislas. 2013. “Inside the letterbox: how literacy transforms the human brain.” Cerebrum: the Dana forum on brain science, 2013(7).

- Ehri, Linnea C., and Sandra McCormick. 1998. “Phases of Word Learning: Implications for Instruction with Delayed and Disabled Readers.” Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties 14, no. 2 (April–June): 135–64.

- Nittrouer, Susan, et al. “What Is the Deficit in Phonological Processing Deficits: Auditory Sensitivity, Masking, or Category Formation?” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 108, no. 4 (2011): 762-785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2010.10.012.

- Sargiani, R.D.A., Ehri, L.C., & Maluf, M.R. (2021). “Teaching Beginners to Decode Consonant-Vowel Syllables Using Grapheme-Phoneme Subunits Facilitates Reading and Spelling as Compared With Teaching Whole-Syllable Decoding.” Read Res Q, 00(00), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.432

- Seidenberg, Mark S., and James L. McClelland. “A Distributed, Developmental Model of Word Recognition and Naming.” Psychological Review 96, no. 4 (January 1, 1989): 523–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.96.4.523.

- Stanovich, Keith E., and Richard F. West. “Exposure to Print and Orthographic Processing.” Reading Research Quarterly 24, no. 4 (September 1989): 402. https://doi.org/10.2307/747605.

- Zarić, Jelena, Marcus Hasselhorn, and Telse Nagler. “Orthographic Knowledge Predicts Reading and Spelling Skills Over and Above General Intelligence and Phonological Awareness.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 36, no. 1 (February 5, 2020): 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00464-7.