How writing and reading work together: The key to strengthening literacy skills

Writing and reading are deeply connected, and strengthening both together helps learners build broader literacy skills and deeper understanding. When instruction intentionally links these practices, students become more confident communicators and stronger, more capable readers.

A post from our Literacy learning: Science of reading blog series written by teachers, for teachers, this series provides educators with the knowledge and best practices needed to sharpen their skills and bring effective science of reading-informed strategies to the classroom.

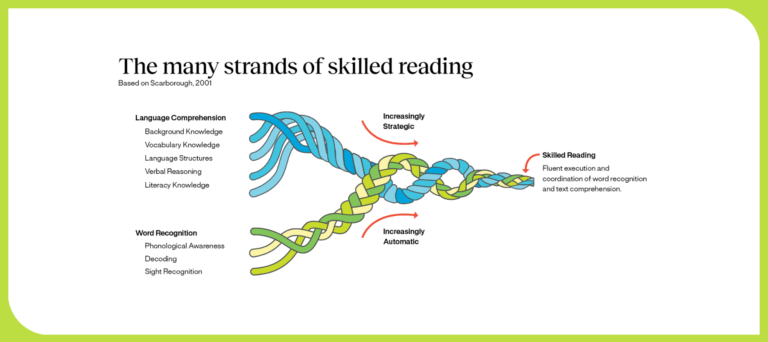

Reading and writing are not separate skills operating in isolation—they are interconnected processes that strengthen each other in powerful ways. When we understand how the brain processes literacy, we see that specific areas handle oral language processing while other regions manage written language forms. By engaging in both reading and writing, students move back and forth between these neural pathways, creating stronger connections.

Jennifer Delano-Gemzik, EdD, literacy expert and consultant for 95 Percent Groups reminds us that sound mapping capabilities guarantee decoding capabilities, but the opposite isn’t true. “Just because a student can read a word doesn’t mean they can write it or spell it correctly—but if they can spell it, they can decode it.” When students can correctly map the sounds in a word, they’ve established a more robust neural highway in their brain, creating deeper pathways for literacy success than reading practice alone can provide.

The role of writing in literacy development

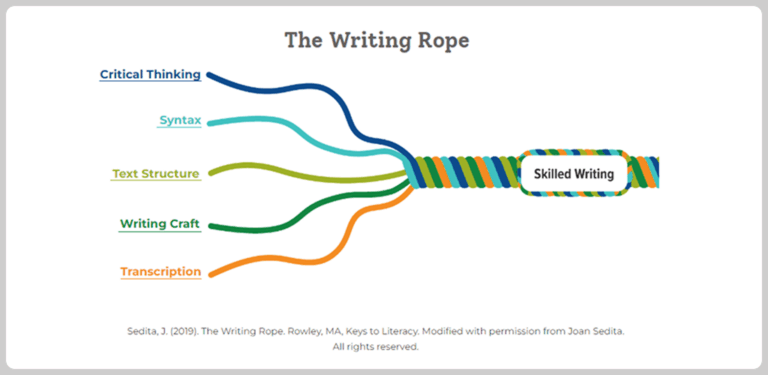

Writing plays an essential role in literacy development, serving as both a foundation for academic success and a tool for lifelong learning. Understanding how writing works requires recognizing that it encompasses two distinct but interconnected components, as outlined in Joan Sedita’s writing rope framework.

Jennifer Delano-Gemzik, EdD

Transcription

The first component consists of transcription skills—the foundational abilities that allow students to physically produce written language. These include letter formation, understanding concepts of print like spacing between words, handwriting fluency, spelling accuracy, and proper use of capitalization and punctuation. Studies have shown that the level of automaticity that students (and adults!) developed over time has a significant impact on the working memory, and subsequently on “higher order processes” required for writing. These transcription skills must become automatic and fluent, much like the word recognition skills on the bottom half of the reading rope.

Tier 1 phonics programs like 95 Phonics Core Program and Tier 2 resources like 95 Phonics Lesson Library explicitly teach handwriting to automaticity, providing students with systematic instruction, contextual guided practice, and application opportunities until these skills become second nature. These programs also teach both encoding and decoding, securing the spelling accuracy needed for fluent composition.

Composition

When students achieve fluency in transcription skills, they free up cognitive bandwidth to focus on the second component: composition skills. “This mirrors what happens in reading development,” Gemzik said. “When students become proficient, automatic decoders, they can dedicate more mental resources to comprehension and higher-order thinking processes.” This is precisely why mastering foundational skills—like letter formation and spelling—is so critical in grades K-5. Students need these skills to become automatic so their brains can transition to the more complex, metacognitive tasks required for effective composition.

The science behind reading and writing

The cognitive science underlying reading and writing offers insights about how these processes support each other. Different regions of the brain activate during literacy tasks—with writing requiring the integration of multiple simultaneous processes. This integration strengthens neural pathways.

Vocabulary and oral language development play a critical role in this process. Gemzik gave us an example of this. “Generally, in order for students to be able to write a sentence, they have to have experience using it orally—emphasizing the importance of building rich oral language skills. However,” she continued, “the relationship between oral and written vocabulary changes as students progress through school. Initially, children enter school with much stronger oral language skills than print-based skills. Then, around third or fourth grade, a significant shift occurs—students’ print vocabularies begin to exceed their oral vocabularies as they navigate increasingly sophisticated texts.” The vocabulary growth through reading supports students’ ability to use that same vocabulary in their writing.

This shift also highlights the importance of sentence expansion strategies. Through read-alouds and explicit instruction, students learn to analyze complex sentences, understanding how words and phrases function within sentences in order to communicate meaning. This analytical work on syntax is what helps lead students to write complex sentences themselves.

How writing improves reading skills

Writing supports reading development across multiple domains, creating reciprocal language benefits that strengthen overall literacy competence.

Phonemic awareness development

Reading and spelling share a reciprocal relationship in the foundation of phonemic awareness. As students develop awareness of individual sounds (phonemes), they must understand that letters represent these sounds. Conversely, as they learn about letters, they strengthen their understanding that letters represent the individual sounds they hear in words. This dual reinforcement secures phonemic awareness beyond what either reading or spelling instruction could accomplish alone.

Programs like Kid Lips (included in the 95 Phonemic Awareness Suite™), and 95 Pocket PA™ don’t stop at the sound level—they systematically connect sounds to their print representations. Students don’t just look at letters; they write them while simultaneously saying the corresponding sounds. This multimodal approach helps students work toward automaticity in sound-spelling connections.

Vocabulary and language development

Writing demands precision in language use that speaking often doesn’t require. “When students write,” Gemzik explained, “they must choose words that express exactly what they mean, leading to more deliberate vocabulary choices and deeper word knowledge. This specificity requirement pushes students to expand their vocabularies and develop more sophisticated language structures.”

The act of writing also helps students internalize sentence patterns and grammatical structures they encounter in reading. As they practice constructing sentences, they develop intuitive understanding of how language works, which transfers directly to reading comprehension.

Critical thinking and comprehension

Writing requires students to organize thoughts, make connections between ideas, and present information logically. These critical thinking processes directly support reading comprehension skills. When students write about what they read, they have to be able to process information more deeply, analyze relationships between concepts, and synthesize understanding—comprehension processes that are central to reading and meaning making with more complex texts.

Gemzik gives this example. “Research has shown the importance of having students read and break down complex sentences to understand the role of words and phrases within sentences—how they are used to communicate meaning—so that they can then effectively use complex sentences in their own writing.”

4 Strategies to integrate writing into literacy instruction

At the basic level, a lot of times we forget that [writing] does need to be explicit for students. I think sometimes, we expect them to just get it through immersion. But the reality is that they have to have experiences—as well as rich oral language skills—that they can draw on themselves. And even then, teachers still need to model that process for students from the very beginning.

Jennifer Delano-Gemzik, EdD

1. Systematic skill building

Effective writing instruction is explicit and systematic. Students need modeling of the entire writing process, from sentence construction to expansion and combination. Teachers demonstrate how to plan for different writing purposes and provide guided practice before expecting independent application.

While rich language immersion experiences matter, the research emphasizes moving beyond immersion approaches to writing instruction. Students need explicit instruction in the mechanics and processes of effective writing. This includes everything from letter formation and sound-spelling mapping to sentence dictation and construction practice, to complex planning strategies for extended writing tasks.

For English learners and students with still-developing oral language skills, scaffolds like sentence starters and sentence stems reduce cognitive load while supporting complete sentence construction in writing.

2. Intentional writing across content areas

Writing serves multiple purposes beyond literacy development—it can significantly deepen students’ understanding in different content areas. When students write about science concepts, historical events, or even mathematical processes, they have to organize their knowledge and articulate their understanding clearly. This process reinforces both previous content knowledge and the learning of new concepts, while simultaneously further developing writing skills.

Programs like Morpheme Magic encourage students to apply morphemic knowledge across content areas. Gemzik offers this example. “If students are studying the prefix “un-” while reading Hatchet (for example), they might identify words with this prefix throughout the text and use five of them to write about events in the story, connecting morphological awareness with both reading and content understanding.”

3. Daily morpheme application

Additionally, Morphemes for Little Ones (specifically for students from K-3) emphasizes daily writing practice using target morphemes. The program includes extensive oral language development—students say morphemes, use them in sentences, and engage with picture cards featuring discussion prompts. This oral foundation supports the daily writing practice that helps students internalize morphemic patterns.

4. Responses to literature

There are many ways to respond to literature, such as literature circle discussion, character analysis, story mapping, or “book talk” presentations. One unique activity is Pen-Pal Responses to Literature.

This idea is based on the classic classroom-to-classroom pen pals activity—but with an added conversation about literature. Developing a literacy partnership between two classes provides students with an opportunity to form real connections with peers while also practicing the skill of writing about reading. Students are paired with peers in another class who have similar reading interests and can then engage in dialogue (both oral and written) about what they are reading.

Not only does this offer an opportunity for authentic practice, it also offers wider exposure of new and different texts for all students.

Putting it all together

At its foundation, effective writing instruction recognizes that students need explicit teaching rather than expecting skills to develop through immersion alone. Students thrive when they have experiences to draw upon and rich oral language skills as prerequisites for writing success. From there, they need systematic modeling of writing processes—how to construct sentences, expand ideas, combine thoughts, write for different purposes, and plan effectively.

The reciprocal relationship between reading and writing creates a powerful cycle of literacy development. As students engage with well-written texts, they internalize language patterns and structures they can apply in their own writing. As they practice writing, they develop deeper appreciation for the craft decisions authors make, enhancing their reading comprehension and analysis skills.

The key lies in understanding that both transcription and composition skills matter, that explicit instruction accelerates development, and that the integration of reading and writing creates learning opportunities greater than the sum of their parts. When educators embrace this integrated approach, they provide students with the strongest possible foundation for literacy success across all academic areas and throughout their lives.

By recognizing writing as a powerful tool for improving reading skills, educators can create more comprehensive, effective literacy instruction that serves every student’s path to becoming a confident, capable reader and writer.

Expert Biography

Jennifer Delano-Gemzik, EdD has worked in education for the past 25 years as a National ELA consultant and trainer for schools and districts on topics related to the Science of Reading and implementing evidence-aligned instruction. Before joining the 95 Percent Group, Gemzik worked as a national ELA consultant for the Consortium on Reaching Excellence, a National LETRS facilitator, and as a private consultant. She is a North Carolina state certified trainer for Reading Research to Classroom Practice as well as a Dyslexia Delegate. She has served as a member of North Carolina’s ELA Advisory Committee, and as a proud parent of two children with special needs, she has volunteered with a state parent advisory group to advance literacy legislation in the state. She has also worked as an elementary school administrator, literacy coach, classroom teacher, and English as a Second Language teacher in North Carolina and overseas with the Peace Corps.

Sources

- López-Escribano, C., Martín-Babarro, J., and Pérez-López, R. “Promoting Handwriting Fluency for Preschool and Elementary-Age Students: Meta-Analysis and Meta-Synthesis of Research From 2000 to 2020.” Frontiers in Psychology 13 (2022): 841573. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.841573.

- Moran, Renee, and Monica Billen. 2014. “The Reading and Writing Connection: Merging Two Reciprocal Content Areas.” Georgia Educational Researcher 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.20429/ger.2014.110108.

- Wierschem, Jenny. 2019. “What Is the Language Literacy Connection for Skilled Reading? – International Dyslexia Association.” International Dyslexia Association. December 20, 2019.

- WWC | Teaching Elementary School Students to Be Effective Writers.” n.d. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/WWC/PracticeGuide/17.