Scarborough’s Reading Rope: A practical guide for building skilled readers

Scarborough’s Reading Rope unpacks the many strands that contribute to skilled reading and offers practical guidance for strengthening each one. When educators use this framework with intentional instruction, students build the integrated skills needed for fluent, confident reading.

A post from our Literacy learning: Science of reading blog series written by teachers, for teachers, this series provides educators with the knowledge and best practices needed to sharpen their skills and bring effective science of reading-informed strategies to the classroom.

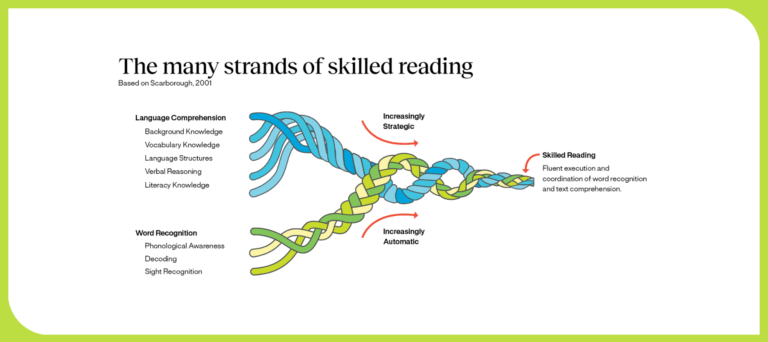

Scarborough’s Reading Rope, developed by Dr. Hollis Scarborough in 2001, visually illustrates skilled reading. Dr. Scarborough originally used pipe cleaners to represent how various components of literacy intertwine. The rope is divided into eight key elements, grouped into upper and lower strands, which work together to form the foundation of skilled reading.*

Understanding the structure of the reading rope

The upper strands of Scarborough’s Reading Rope are related to language comprehension, and the lower strands involve word recognition. While the upper strands are available to readers in increasingly strategic ways, the lower strands can be mastered through explicit instruction, becoming increasingly automatic over time.

The upper strands of the rope are never fully complete; we continue to develop these over time as we have life experiences. According to Samantha Chatman, implementation manager at 95 Percent Group, “These are skills that we continue to develop over time. Even as adults, we’re still developing background knowledge in certain topics and improving vocabulary. The upper strands will constantly grow as we become more skilled readers.”

On the other hand, the bottom strands are rooted in word recognition. Once a young reader learns these skills, they begin to recognize patterns automatically. Although we continue to add words to our mental lexicon, “there is a point where the skills at the bottom part of the rope should no longer need to be explicitly taught,” Samantha continues, “There is a top end to those skills once readers develop automaticity.”

Breaking down the lower strands: word recognition

The lower strands of Scarborough’s Reading Rope—phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition—form the foundation of word recognition. Word recognition requires subskills that are typically taught to students as early as preschool.

Phonological awareness

Phonological awareness refers to the awareness of larger units of spoken language, such as syllables and onset-rime, and smaller units, phonemes. Phonemic awareness is critical in reading development as it helps students understand that words are made up of individual sounds.

In the classroom, teachers may ask students to segment a word to identify the individual sounds (cat –/k/ /ă/ /t/) or change one sound for another (change cat to bat). Activities like these strengthen students’ ability to identify and manipulate sounds, preparing them for successful decoding and encoding (spelling)

Decoding

Decoding is understanding the alphabetic principle and sound-symbol correspondences–or the idea that each sound (phoneme) is represented by a letter (grapheme) or group of letters—to efficiently unlock the written word (this is where phonics instruction comes into play).

Teachers help students build early decoding skills by identifying the sounds (phonemes) in a word (/b/ /a/ /t/), then representing those sounds with letters (graphemes): bat.

Sight recognition

Sight recognition refers to the automatic recognition of learned words and spelling patterns. Word automaticity is what allows the brain to devote cognitive resources to the ultimate goal of reading—comprehension.

Sight recognition is achieved through a process of orthographic mapping: “When readers apply their grapheme-phoneme knowledge to decode new words, connections are formed between the graphemes in written words and the phonemes in spoken words. This bonds the spellings of those words to their pronunciations and meanings, and stores all of these identities together as lexical units in the memory. Subsequently, when these words are seen, readers can read the words as single units from memory automatically by sight” (Sargiana, R.D.A, et.al., 2021). So to support that process, explicit instruction in phoneme-grapheme correspondences and meanings and pronunciations of words is important, with lots of opportunities to practice.

Breaking down the upper strands: language comprehension

Before they come to school, students begin developing language comprehension skills naturally through conversations at home and social interactions. While instruction in the word recognition skills is a focus of primary reading instruction, background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge are developed and enhanced throughout the school experience and beyond.

Background knowledge

As students develop background knowledge, they build broad knowledge of a topic through lived experiences or classroom activities. The amplification

of children’s exposure to new topics and vocabulary is essential for developing comprehension. Their knowledge base helps them continue to make sense of new ideas and experiences.

Samantha Chatman explains, “Building background knowledge is designed to pique the students’ interest in a topic. It also ensures they have adequate prior knowledge to make connections to the text that they’re currently reading.”

Examples of strengthening background knowledge include showing children videos about topics they’re learning, taking a poll of their opinions and having informal discussions, and developing K-W-L charts to cover what they know, want to know, and have learned.

Vocabulary

Vocabulary refers to a person’s knowledge and understanding of word meanings and is typically divided into two types: receptive vocabulary (words we understand when we hear or read them) and expressive vocabulary (words we use when speaking or writing).

Samantha Chatman comments further, “When children enter school, they usually have a large oral vocabulary but a much smaller reading vocabulary. At some point, this shifts. By fourth or fifth grade, many students recognize and understand more words in print than they use in conversation. This trend continues into adulthood—most of us know far more words through reading than we regularly use in speech.” Similarly in the early years, most vocabulary is developed through oral language; as we enter the middle years, we develop most new vocabulary through reading. So oral language development AND wide reading are both important.

Vocabulary is both “caught” (through discussion, read-alouds, experiences, etc.) and “taught.” For example, teachers may implement morphology activities, which involve identifying prefixes, suffixes, and root words. They may give children three prefixes, three suffixes, and one base word and ask them how many words they can make. Then, they may define the words or use them in a sentence to build understanding.

While children don’t have to know the definition of every word, morphology is critical in helping them unlock word parts and make meaning.

Language structures

To help students learn to analyze words down to the letter sounds and spelling patterns (something a good reader does unconsciously), teachers must have thorough knowledge of language structure from phonology all the way through morphology, syntax, and text structure.

As an example, to strengthen language structures, teachers may give students a word with multiple meanings and ask them to create sentences with it in different contexts.

Verbal reasoning

Verbal reasoning involves the mental processes we use to understand language beyond the literal meaning, including making inferences, interpreting metaphors, and drawing conclusions from context.

To strengthen verbal reasoning skills, teachers often use think-aloud strategies. During a read-aloud, they pause to model their thought process, as they share inferences, questions, or connections aloud. Students may then practice this skill by turning to a partner to discuss what they’re thinking as they read, helping them become more aware of how they construct meaning from text.

Literacy knowledge

Literacy knowledge encompasses the knowledge of print concepts, genre, and everything that falls into the purposes, features, and conventions of text. Having a depth of understanding about texts can begin at a very early age with simple read-aloud activities. Reading with children helps them understand how to hold a book, that the text moves from left to right and top to bottom, and that books usually have an author and an illustrator. All of this early knowledge contributes to skilled reading as children progress.

How teachers and schools use Scarborough’s Reading Rope

Scarborough’s Reading Rope is a valuable framework for understanding the complexities of skilled reading. It helps educators identify which strands of reading may be incomplete for students and helps them understand where to focus instruction.

In practice, teachers use Scarborough’s Reading Rope to:

- Understand skill gaps: When a student falls behind, the rope helps trace the challenge to a specific area of need. For example, a fourth-grade student struggling with reading comprehension might need to revisit foundational decoding skills typically taught in first grade. While diagnostic assessments pinpoint skill gaps and point to instruction, the Rope helps educators understand the skills and how they fit within the entire endeavor of skilled reading.

- Guide instructional decisions: Once an area of weakness is identified, the rope is just the beginning. Educators can use targeted assessments, like a phonics or phonological awareness screener, to dig deeper and guide intervention planning.

- Explain deficiencies to parents: The graphic is a helpful guide for teachers to show parents where a child may be struggling. Teachers and parents can work together to plan at-home activities to develop a skill.

- Reflect on teaching practices: The rope offers a lens for educators to evaluate whether their current instruction aligns with evidence-based strategies. It can prompt necessary adjustments to ensure students receive structured, systematic, and explicit literacy instruction.

Solutions to put Scarborough’s Reading Rope into practice

At 95 Percent Group, our suite of evidence-based tools and resources is designed to strengthen every strand of Scarborough’s Reading Rope, ensuring educators can deliver effective, targeted instruction across all components of reading.

- Phonological Awareness: Tools like the Phonemic Awareness Screener for Intervention (PASI) and Phonemic Awareness Intervention Resource (PAIR) help educators assess and teach essential sound awareness skills for early and struggling readers.

- Decoding and Sight Recognition: 95 Tier 2 Phonics Solution, which includes 95 Phonics Lesson Library™ 2.0 and95 Literacy Intervention System™, supports explicit, systematic phonics instruction and word-level reading interventions across all tiers. These tools guide instruction from initial decoding through to automatic word recognition.

- Vocabulary and Morphology: Spellography™ and our morphology lessons provide structured instruction in word parts, enhancing vocabulary through deep understanding of word origins and structure.

- Language Comprehension: Resources such as the Top 10 Tools™ professional learning series equip teachers with the background knowledge and strategies needed to foster comprehension through verbal reasoning, language structures, and literacy knowledge.

- Instructional Reflection and Planning: Our digital platform and screeners support data-driven decisions, helping teachers pinpoint strand-specific needs and implement appropriate interventions at scale.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope provides a powerful framework for understanding the complexities of skilled reading. By breaking down reading into its key components, educators can pinpoint areas of need and tailor instruction to support every student’s growth. With the right tools and targeted interventions, teachers can help students master each strand of the rope, ultimately fostering confident, proficient readers. By integrating evidence-based practices with Scarborough’s Reading Rope, we can ensure that all students develop the skills they need to become successful lifelong readers.

Expert Biography

Samantha Chatman, Implementation Manager

Samantha Chatman is an experienced educator from Columbus, Ohio, with 19 years in the field, including five years as a district administrator. She previously served as the Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, where she championed inclusive practices across the district. Samantha is also a seasoned coach and consultant specializing in the Science of Reading and Structured Literacy. Currently, she serves as an Implementation Manager, bringing her deep expertise in education and leadership to drive impactful change.

Sources

*Scarborough, Hollis S. “Connecting Early Language and Literacy to Later Reading (Dis)Abilities: Evidence, Theory, and Practice.” In Handbook for Research in Early Literacy, edited by Susan Neuman and David Dickinson. New York: Guilford Press, 2001.