Reading disabilities: Signs, types, and tips to help students succeed

Reading is a foundational skill—critical for both academic success and lifelong learning. However, for some individuals, the path to unlocking literacy can be challenging due to reading disabilities. These disabilities, often referred to as reading disorders or reading impairments, can significantly impact a student’s experience when learning to comprehend and process written information. In this article, we’ll examine reading disabilities, explore their signs, various types, and most importantly, provide valuable tips to support students in overcoming these challenges.

What are reading disorders?

Reading disorders encompass a range of learning difficulties that affect an individual’s ability to read fluently and comprehend written text. They can stem from various factors, including neurological differences and genetic factors. Most reading disorders result from specific differences in the way the brain processes written words and text. People with reading disorders often have problems recognizing words they already know and understanding text they read. A reading or language disorder can also impact a person’s spelling. It is important to note that not everyone with a reading disorder has every symptom.

It’s critical to understand that reading disorders are not a type of intellectual or developmental disorder, and they are not a sign of lower intelligence or laziness. It’s common that individuals with reading impairments may have other learning disabilities, including problems with writing (dysgraphia) or numbers (dyscalculia), or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

The most common reading disorders include dyslexia, dysgraphia, and specific reading comprehension deficits. There’s no cure for reading disorders, but by recognizing them early in their education students can be taught ways to manage these challenges and become effective readers.

Signs of a reading disability

The signs of having a reading disability can vary for each individual. Although it can present itself in many different ways, five commonly observed issues tend to point to a reading disability. Knowing the signs is crucial to helping students with early intervention.

- Challenges with phonological and phonemic awareness skills: This can present itself when it comes to skills such as rhyming and being able to isolate single sounds in a word. Students having issues with this may not be able to easily break down or understand compound words.

- Issues decoding words: Students struggling with decoding may struggle to discriminate letters correctly by confusing letters that look similar such as (b, p, and d). Decoding issues may also make it hard for students to sound out words while reading. One sign of this is when students start memorizing words or relying on photos to identify the word without truly decoding it.

- Struggling with fluency: Fluency issues will be noticeable when reading out loud. Those struggling with fluency may lack expression when reading and have trouble recognizing punctuation within and between sentences.

- Problems with reading comprehension: If students are working too hard to understand each word in a sentence, they may then struggle to grasp the text. This could lead to confusion as to what they’re reading and cause students to have issues understanding the main idea. A sign of this is that students may get caught up in unimportant minor details or skip and miss important details.

- Reluctance or avoidance of reading-related tasks: As students deal with more reading difficulties, there is a significant risk of students not wanting to participate in reading-related activities. Students may deal with feelings of embarrassment and frustration. They may even try to misbehave to try to avoid having to read.

“Identifying a reading disability can be challenging for several reasons: children develop reading skills at different rates, reading difficulties can be masked or complicated by other factors such as ADHD, the complexity of the reading process, and how the multiple skills manifest differently in different individuals,” said Laura Stewart, Chief Academic Officer of 95 Percent Group.

With younger children, one of the first signs is often a working memory deficit. For example, being unable to quickly identify shapes or well-known objects may be a first indication of a reading impairment. This is why a Rapid Automatic Naming (RAN) screen can be so useful—it offers a way to collect information before children fully know letter names and shapes (another common screen for dyslexia).

Identifying signs of a reading disability is crucial for early intervention and support. With early identification of students that are at-risk for a reading disability (especially dyslexia), intervention can begin immediately—significantly increasing the chances that all students can be reading on grade-level by 3rd or 4th grade. Research shows that if children are not reading at grade level by 4th grade, the chances of becoming a confident, fluent reader are far less.

Types of reading disabilities

A large percentage (around 70-80%) of struggling readers have weaknesses or gaps in phonological processing, and often have problems in tandem concerning fluency and comprehension. These individuals have trouble learning how sounds relate to written symbols, affecting their ability to both sound out words and spell correctly.

Another subgroup of struggling readers can decode words and still have trouble making meaning or deriving information from a text. Unlike those who are often considered to have dyslexia, these individuals can read words quickly and with accuracy. Their challenges, however, sometimes lie in difficulties related to social knowledge or social reasoning (social knowledge is one of the most important social competences and could be defined as the ability to analyze and reason about social situations in relation to social rules), abstract verbal reasoning, or language comprehension.

Reading impairments are sometimes broken down into three subcategories:

- Phonological deficit: affecting the processing of oral language sounds

- Processing speed/orthographic processing deficit: impacting the speed and accuracy of recognizing printed words

- Comprehension deficit: often observed in children with social-linguistic disabilities (e.g., autism spectrum), vocabulary weaknesses, language learning disorders, and difficulties in abstract reasoning and logical thinking

These can exist singularly or a person can be dealing with more than one of these deficits.

Three of the most common reading disabilities:

Dyslexia

- One of the most common reading disorders, dyslexia involves difficulties in accurate and fluent word recognition along with an inability to recognize and incorporate grammar and syntax. Individuals with dyslexia may have trouble with decoding words, spelling, and often with writing as well. Most have normal, or even sometimes above average intelligence but read at levels significantly lower than expected. This is one of the more common indicators if it is not identified early on. Although the disorder varies from person to person, there are common characteristics: People with dyslexia often have a hard time sounding out words, understanding written words, and naming objects quickly. There are different ways to teach students with dyslexia in the classroom and at home.

Alexia

- Most reading impairments are present from the time a child learns to read. But some people lose the ability to read after a stroke or an injury to the area of the brain involved with reading. People with this disorder often also have another disorder called agraphia, which means they are no longer able to write as well. Through teaching strategies such as repetition, those dealing with this disorder can work to read again.

Hyperlexia

- This particular reading disorder is where people have advanced reading skills but may have problems understanding what is read or spoken aloud. They may also have cognitive or social problems such as autism. However, not everyone who has autism will have hyperlexia. Those with hyperlexia may benefit from teaching methods such as visual aids and word association games.

Reading disorders can also involve problems with specific skills:

Word decoding

- People who have difficulty sounding out written words struggle to match letters to their proper sounds. This becomes especially pronounced in upper elementary when multisyllabic words are more common in texts.

Fluency

- When people struggle to read with fluency, it is usually in large part because they are still expending a lot of effort on decoding words. One of the foundations of fluent reading is automatic word recognition. Without this, it’s difficult to connect ideas to background knowledge which is a necessary part of deep reading comprehension.

Poor reading comprehension

- People who struggle with reading comprehension have trouble connecting to what they are reading. Comprehension requires the mind to be free of the labor of decoding.

How to Help Students with Reading Disabilities

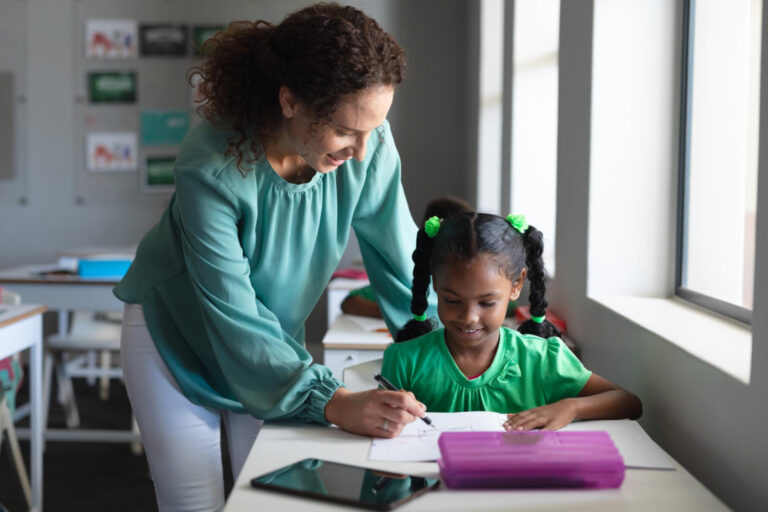

Supporting students with reading disabilities involves a multifaceted approach that combines patience, understanding, and targeted strategies.

“A major challenge is that parents and teachers may not always have adequate training or awareness to recognize the signs of a reading disability, so teacher preparation and professional learning in this area are critical,” explains Chief Academic Officer Laura Stewart. “We also know that early identification is of the utmost urgency, so that students can get what they need as early as possible; a significant challenge may be the lack of systematic screening for reading disabilities or the use of only universal screeners in assessing students. Refined, precise diagnostic screeners, utilized early on as part of a comprehensive assessment cycle must be in place.”

Here are five some effective tips to teach students facing reading disabilities:

Screening to identify risk:

- Children can be screened for risk of reading disabilities as early as preschool and kindergarten. The earlier you know, the sooner you can help.

Early intervention:

- Identify and address reading difficulties as early as possible to provide tailored interventions suited to individual needs.

Multisensory learning:

- Implement teaching methods that engage multiple senses, such as sight, sound, and touch, to reinforce reading skills.

Structured literacy programs:

- Utilize evidence-aligned programs that systematically teach phonics, decoding, and comprehension skills.

Assistive technology:

- Introduce tools like digital intervention programs, text-to-speech software, or specialized reading apps to aid in reading and comprehension.

Additional resources

Finding additional support and resources for individuals with reading disabilities and those assisting them is essential. Here are some valuable resources:

- Webinar: Introducing the 95 Literacy Intervention System

- Webinar: Tier 3 in the One 95™ Literacy Ecosystem™: Proven Instruction That Works!

- Webinar: I have beginning-of-the-year data, now what?

- Webinar: Introducing the 95 Phonemic Awareness Suite

- Webinar: How the brain reads: Highlighting the work of Dr. Stanislas Dehaene

- Webinar: Achieving Success with MTSS: Supporting all students in Tiers of Instruction

- The Reading League: On a mission to make sure all children can learn to read and all teachers can learn to teach them. Offers conferences, professional development, and downloadable resources

- International Dyslexia Association (IDA): Offers information, resources, and support for individuals with dyslexia and their families

- Understood.org: Provides comprehensive information, tools, and a supportive community for parents and educators dealing with learning and attention issues

The final word

Understanding and supporting students with reading disabilities is a collaborative effort that involves strong partnership and commitment among educators, parents, and the community. By recognizing the signs, understanding the types, and implementing effective strategies, we can create an inclusive environment where every student has the opportunity to thrive in their reading journey.

With early identification, effective interventions, and a supportive network, individuals with reading disabilities can develop the necessary skills to become proficient readers and achieve their full potential.

Resources

- Hulme, Charles, and Margaret J Snowling. “Reading Disorders and Dyslexia.” Current opinion in pediatrics, February 1, 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5293161/.

- “What Are Some Signs of Learning Disabilities?” Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, September 11, 2018. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/learning/conditioninfo/signs#dyscalculia.

- “Types of Reading Disability.” Reading Rockets. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://www.readingrockets.org/topics/struggling-readers/articles/types-reading-disability.

- Moats, L, & Tolman, C (2009). Excerpted from Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS): The Challenge of Learning to Read (Module 1). Boston: Sopris West.

- Barisnikov K, Lejeune F. Social knowledge and social reasoning abilities in a neurotypical population and in children with Down syndrome. PLoS One. 2018 Jul 20;13(7):e0200932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200932. PMID: 30028865; PMCID: PMC6054403.

- “Stroke.” Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, February 1, 2022. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/stroke.

- “Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI).” Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, November 24, 2020. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/tbi.

- Ostrolenk, Alexia, Baudouin Forgeot d’Arc, Patricia Jelenic, Fabienne Samson, and Laurent Mottron. “Hyperlexia: Systematic Review, Neurocognitive Modelling, and Outcome,” May 3, 2017.

- Cherney, Leora Reiff. “Aphasia, Alexia, and Oral Reading – Pubmed.” National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=14872397.