Early literacy: What it is, why it matters, and how to support it

Early literacy lays the foundation for lifelong learning by developing the key skills children need to read with fluency and comprehension, and this post breaks down what it is, why it matters, and practical ways educators and families can support it.

A post from our Literacy learning: Science of reading blog series written by teachers, for teachers, this series provides educators with the knowledge and best practices needed to sharpen their skills and bring effective science of reading-informed strategies to the classroom.

Learning how to read is arguably one of the most critical skills a child will learn in their life. It’s not just the key to academic success, but also a pathway to agency and joy. Science of reading research and evidence has shown us that literacy skills are built on the foundation of oral language. We now know that oral language development actually begins before birth—the growing child responds to oral language while still in utero.

It’s clear today that language development in the first three years of life lays the foundation for literacy acquisition. This foundation continues to be built upon or not, to be fostered and nourished or not, until a child arrives at school for the first time. And this is where we really see the differences.

There is a proven connection between reading and writing and oral language in developing early literacy. As parents and teachers there is so much we can do to help children arrive at school with the language and confidence they need to begin to learn to read.

The key components of early literacy

While we are clear that literacy development actually begins with language development, the teaching of early skills to support literacy development usually begins in the preschool years—ranging from age three to age five.

Looking at what the components of early literacy are, it’s easy to say that as with the structured literacy approach, it would be the instructional content of the domains of language as they pertain to reading and writing (see the Structured Literacy infographic from International Dyslexia Association).

But when we zoom in on the three to five age range, it looks a bit different.

- Concepts of print: Learning about books, how to hold them, what a letter, a word, and a sentence is, how we read from left to right and top to bottom

- Phonological awareness: The larger sound structures like hearing syllables in a word, onset-rime, and rhyming skills

- Phonemic awareness: identifying and manipulating the smallest sounds in words)

- Alphabetic principle: sound/symbol association where children learn the graphemes (letters) that represent the phonemes (sounds) (i.e., the letter A spells /ǎ/).

- Oral language skills:

- Vocabulary and knowledge building: vocabulary acquisition is essential to learning to read. When children first begin reading words, they are essentially decoding words they’ve already heard, can say, and might even know the meaning of. This is what ties decoding to eventual reading comprehension.

- Fine motor skill development: helps prepare children for handwriting instruction

Literacy expert and consultant for 95 Percent Group, Kayla Hindman, weighed in on these ideas. “When we think of ‘early literacy’ we truly need to connect everything we do back to oral language skills. Children need exposure across a variety of topics to understand the world around them and aid in building background knowledge that will later impact their reading comprehension.”

Why is early literacy important?

When children have a solid early literacy and oral language foundation, they almost always go on to have success in acquiring more sophisticated literacy skills. Early literacy instruction is truly the building block for reading, writing, and speaking.

When we foster the opportunities for children to be in an environment where they will have access to robust oral language experiences as well as environments in which reading and writing are both modeled and taught, we are setting kids up for success to be fluent readers and writers—and to be good speakers, listeners, and communicators.

Early literacy experiences set the tone and foundation for all learning and academic success.

When children grow up in language-rich environments—where reading, talking, listening, and writing are consistently modeled—they become confident, capable communicators.

What the research shows

While there has been much research surrounding this idea, the thing that has risen to the top is the idea that children develop language through repeated practice with language in conversation. Hindman points out the important part: “The difference in the oral language experience of children who are given many, repeated opportunities to conversate creates a profound impact on vocabulary, background knowledge, phonological awareness, and future reading comprehension.”

The critical part it turns out is the number of conversational opportunities a child has—rather than just isolated incidents of speaking. Hindman explains. “The amount of ‘conversational turns’ with adults is key. It relates back to a child’s oral language development and having rich conversations. For teachers, this means having language rich classrooms as well—classrooms that are full of language being modeled, spoken and listened to.”

It’s the back-and-forth interactions between adult and child that predict brain development and later reading achievement even more strongly than word count alone.

How schools and educators can support early literacy

Hindman explains that strong early literacy instruction can—and should—be woven into everything children do in pre-K, Kindergarten, and first grade. She helps us to see what that can look like across settings.

Play-based learning

Play is not separate from learning—for young children, play is learning. Through structured, play-based learning opportunities, children naturally build vocabulary, background knowledge, narrative skills, and social language.

Strategies for preschool & pre-K

- Play with words: I Spy, rhyming games, clapping syllables

- Play with sounds: Ask children to identify different objects that all start (or end) with the same sound, use sound/picture cards that help to connect the sounds to different objects. By pre-K, children can isolate sounds and begin to identify the sounds inside of words (Easier: what word does /k/-/ǎ/-/t/ make? More challenging: what sounds do you hear in the word cat?)

- Sing songs, chants, and nursery rhymes

- Model concepts of print during read-alouds

- Build vocabulary through rich, thematic units

- Encourage conversations and curiosity (address children with open-ended questions like: “Why do you think…?”)

“Talk to learn” in pre-K

Children need A LOT of talk time, especially interactive talk, to build the knowledge and vocabulary that support early literacy.

Aim for:

- Ample conversational turns (both teacher-to-student and student-to-student)

- Open-ended questions

- Peer-to-peer dialogue

- Rich, academic language exposure

Check out 95 Percent Group’s pre-K specific resource, Talk2Learn!

Designed specifically for Pre-K classrooms, Talk2Learn™ enhances your students’ knowledge of the world, while developing oral language, phonological sensitivity, and phonemic awareness skills.

Kindergarten to early 1st grade: Building foundational skills

At this stage in a child’s schooling, high-quality instruction should include:

- A clear sequence for phonological and phonemic awareness

- Explicit instruction in the alphabetic principle

- Letter-sound correspondence practice

- Blending and segmenting practice using manipulatives or gestures

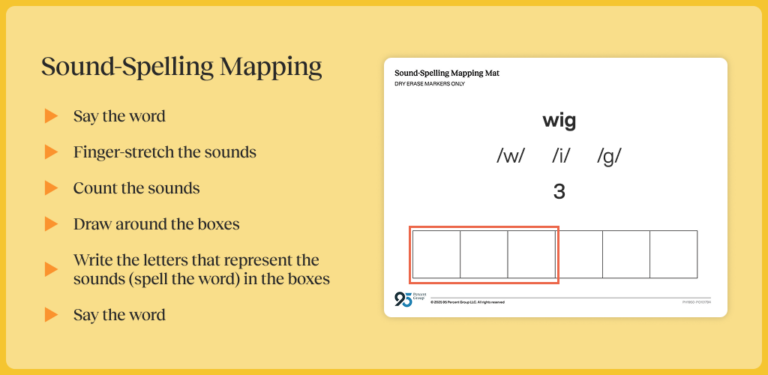

- Finger-stretching to segment phonemes

- Sound-spelling mapping in small-group instruction

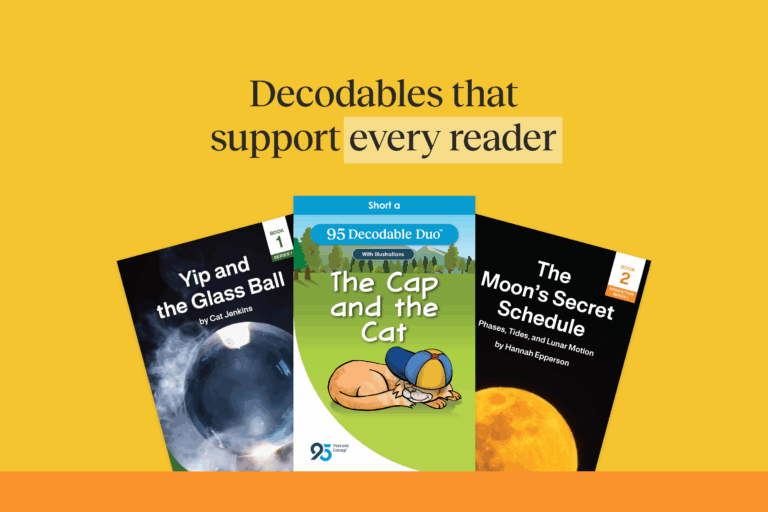

- Opportunities to read decodable text aligned with the relevant phonics patterns

Strong early literacy instruction should be integrated into all activities for pre-K through 1st grade students, utilizing play-based learning to naturally build vocabulary, phonemic awareness, and narrative skills. By weaving these strategies throughout the school day, educators create multiple opportunities for children to develop the critical language and literacy skills they need for reading success.

How parents can foster early literacy at home

Parents play a powerful role in early literacy development—often more than they realize.

Here are research-backed ways to support early literacy at home:

1. Talk—a lot

Narrate daily routines, describe what you’re doing, and introduce new vocabulary naturally. “In order to grow language-related parts of their brain,” Hindman said, “children need to hear language consistently and repeatedly.” It may feel strange at first. But this is how we immerse children in language from the start of their lives.

2. Read aloud every day

Yes, everyone is busy. Time feels scarce. But this is one of the simplest and most important things you can do for your child’s language and literacy development when they are small (and when they’re not so small)! Talk about the pictures, characters, letters, and sounds.

Make it interactive. Ask questions like:

- What do you think will happen next?

- Why do you think they did or said that?

- What do you think that word means?

3. Play sound-based games

- “I spy something that starts with /s/…”

- Clap syllables

- Identify rhyming words

- Repeat silly sound patterns

4. Build both alphabet and sound knowledge

Singing the alphabet song is great—but make sure to emphasize being able to identify both letter names and sounds outside of the song. Discuss letters and the sounds they spell.

5. Make “writing” part of play

Provide crayons, markers, and child-friendly writing tools to develop fine motor skills.

6. Keep conversations going

Children’s language grows through back-and-forth exchanges far more than through passive listening.

Common misconceptions about early literacy

There are several myths that can undermine early literacy development. It’s important to clarify what’s true and what’s not so that every child has the opportunity to enter school ready to learn.

Here are the most common myths:

Myth 1: “Early literacy just means knowing letters and sounds.”

While letters and sounds matter, oral language is the true foundation. Without strong background knowledge and vocabulary, decoding won’t translate into comprehension.

Myth 2: “Memorizing high-frequency words is the best strategy.”

Children shouldn’t memorize words visually.

True automaticity (reading as though by sight) comes from learning the sound-symbol relationships that allow them to decode any word quickly and fluently. This is what eventually frees the cognitive bandwidth for the complex comprehension processes.

Myth 3: “Learning to read is natural—like learning to speak.”

This just isn’t true..

As Louisa Moats, EdD points out in “Learning to Read IS Rocket Science,” while human brains are wired for oral language—reading requires explicit, systematic, sequential instruction plus consistent and repetitive practice to build and strengthen the right neural pathways.

Myth 4: “Handwriting doesn’t matter in early literacy.”

Handwriting supports reading by strengthening phoneme-grapheme connections.

Consistent practice really matters.

Myth 5: “Kids will just pick it up eventually.”

Waiting delays learning. Children need intentional, structured early literacy instruction grounded in evidence.

The power of early literacy

Early literacy is not about rushing children into formal reading instruction. It’s about nurturing the oral language, background knowledge, curiosity, and foundational skills that make reading possible.

From the earliest moments of life, every interaction—every conversation, book, song, rhyme, and shared story—helps wire a child’s brain for literacy.

When we prioritize early literacy, we give children more than reading skills.

We give them access to understanding, opportunity, confidence, and joy.

Expert Biography

Kayla Hindman has worked in education for the past 20 years and has been a consultant for 95 Percent Group for a total of 6 years. Before joining 95 Percent Group, Kayla worked at the Oklahoma State Department of Education as the Early Childhood Director. She has completed all modules of LETRS second edition and was a LETRS facilitator. She has also worked as a classroom teacher, reading interventionist, and literacy coach. Kayla is a proud wife and a parent to her 6-year-old daughter and lives in Texas.

Sources

- Moats, Louisa C. and American Federation of Teachers. 1999. “Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science.” https://www.louisamoats.com/Assets/Reading.is.Rocket.Science.pdf.

- Romeo, Rachel R., Julia A. Leonard, Sydney T. Robinson, Martin R. West, Allyson P. Mackey, Meredith L. Rowe, John D. E. Gabrieli, et al. 2018. “Beyond the 30-Million-Word Gap: Children’s Conversational Exposure Is Associated With Language-Related Brain Function.” Psychological Science 29 (5): 700–710. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617742725.