The urgency of adolescent reading instruction—and why getting it right matters

Adolescent reading instruction matters urgently because middle and high school learners need the skills and support to access complex texts and succeed across subjects. When instruction is purposeful and grounded in the science of reading, students gain the comprehension and confidence they need to thrive.

A post from our Literacy learning: Science of reading blog series written by teachers, for teachers, this series provides educators with the knowledge and best practices needed to sharpen their skills and bring effective science of reading-informed strategies to the classroom.

Many adolescent readers enter middle and high school classrooms already carrying years of frustration and disengagement. Often labeled as disruptive, unmotivated, or defiant, their behavior reflects the reality of students who have repeatedly been asked to do something they were never effectively taught: how to read. Silence, avoidance, or outright defiance can mask a deeper truth—these students have internalized their failure.

When given explicit, evidence-based instruction within a safe, supportive environment, transformation is possible. Students who once resisted begin to participate; those who hid behind silence, start reading aloud. Confidence grows as they finally experience success—and with it comes hope for the future.

Their stories demonstrate that struggling teens are not incapable of learning to read—they are casualties of inadequate instruction, and with the right support, they can and do thrive.

Understanding struggling adolescent readers

Far too many adolescent readers are left behind—angry, disillusioned, and unable to access grade-level work because they were never effectively taught to read. In 2024, only 29% of eighth graders scored at or above the proficient level in reading, the lowest percentage since NAEP began tracking results in 1992 (NAEP, 2024). A large share of middle and high school students still lack foundational reading skills.

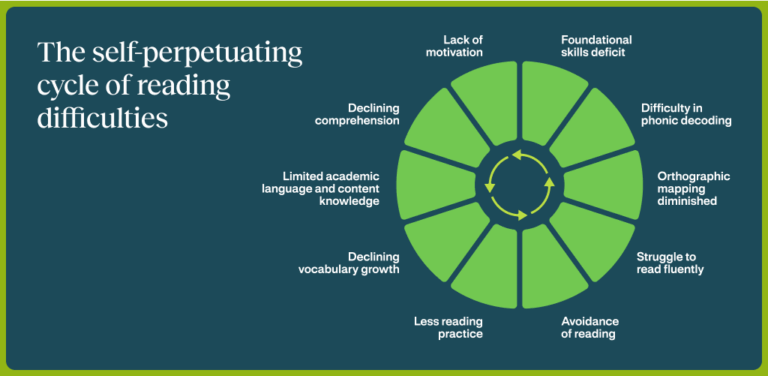

Laura Stewart, Chief Academic Officer for 95 Percent Group, calls this the “self perpetuating cycle of reading difficulties.” When students have foundational skill gaps and can’t access grade level text, they begin to feel inadequate, or like something is wrong with them. This feeling leads to low self confidence and ultimately disengagement with the work which only leads to students falling further behind.

The consequences are profound.

Even for those who finish high school, limited literacy is linked to ongoing academic challenges, restricted career opportunities, and diminished confidence. Adults with low literacy are twice as likely to be unemployed and more likely to live in poverty (NIL, 2008). And strikingly, about 75% of state prison inmates did not complete high school or are classified as low literate (U.S. Department of Education, 2007).

So what must educators and school leaders do to change this trajectory?

We must commit to implementing explicit, evidence-based instructional practices within a supportive system. This includes reliable assessments, progress monitoring, and targeted interventions.

Our students deserve better, and CAN do the work when provided with the right instruction. It is our responsibility to ensure that they graduate not only with a diploma but with the literacy skills needed to thrive in college, career, and life.

The importance of tailored approaches

By middle and high school, students are expected to read and comprehend grade-level texts. Yet, according to the 2024 NAEP fourth-grade scores, only 31% of students perform at or above proficient, with nearly 40% below basic—the highest rate of low performance since 2002 (NCES, 2024). These numbers confirm what educators see daily: many adolescents arrive in secondary classrooms without the foundational skills needed to succeed.

Not only that, teachers routinely have classrooms full of children that sit along a continuum of reading capabilities. A one-sized-fits-all remedy will not suffice.

Importantly, research shows that 95% or more of students can learn to read with effective, evidence-based instruction (Vaughn & Fletcher, 2012).

As Reid Lyon, neuroscientist, specialist in learning disorders, and researcher on the science of reading, explains, “Of the 70% of children who struggle, 95% are ‘instructional casualties,’” meaning their difficulties stem from inadequate instruction, not inherent learning disabilities (Lyon, 2001). Struggling adolescents are not unmotivated or incapable—they have simply not received the teaching they need. With targeted, evidence-based practices, most can still graduate as proficient readers.

This is where tailored approaches become critical.

The American Institutes for Research (AIR) recommends that secondary schools implement Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) that use multiple data sources—such as universal screening, grades, teacher observations, and diagnostic assessments—to identify student needs. Decisions should be made collaboratively, reviewing data regularly and adjusting tier placements as students respond to interventions. In this model, instruction and support are continuously refined, creating a dynamic system that meets students where they are and moves them forward.

Evidence-based instructional strategies for supporting underserved teen readers

Literacy is not limited to reading and writing in English Language Arts (ELA) classes; it is crucial for students to develop the skills necessary to comprehend and communicate effectively in every subject area,such as math, science, and social studies. All educators need to recognize their role as literacy teachers and help students develop the ability to read, analyze, and synthesize information—skills critical for college and career readiness.

When educators embrace their role as literacy instructors, they contribute to supporting students in a more equitable way across the entire school. Literacy is foundational to success in college, careers, and life. It is the key to navigating the complexities of the modern world.

The Institute of Education Sciences (IES) published the IES Practice Guide, a comprehensive guide for improving adolescent literacy, based on a thorough review of over 100 research studies examining evidence-based practices that have been shown to improve literacy outcomes for adolescents. It highlights practices that can be implemented in all classrooms. The two practices with the most substantial evidence that will improve language comprehension are:

- Provide explicit vocabulary instruction.

- Provide direct and explicit comprehension strategy instruction.

Appropriate intervention

The guide encourages educators and leaders to assist adolescent students in improving their decoding and language skills. It emphasizes the importance of providing attentive and individualized interventions which trained specialists can implement for readers needing support:

- Interventions should be explicit, systematic, and data-driven, based on ongoing assessments of student needs.

- Interventions should address foundational reading skills, including decoding, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

Vocabulary instruction

In providing explicit vocabulary instruction, the IES guide emphasizes the importance of directly teaching high-utility words, particularly those essential for understanding complex texts across various subject areas.

- Teach high-utility words directly, especially those needed for complex texts.

- Provide repeated exposure and active use (speaking and writing).

- Teach strategies like analyzing word parts and using context clues.

Comprehension strategy instruction

For direct and explicit comprehension strategy instruction, the IES guide recommends that educators teach students specific, research-backed strategies which include summarizing, making predictions, asking questions, and visualizing to enhance understanding of texts. Instruction should:

- Prioritize specifically modeling strategies such as summarizing, predicting, questioning, and visualizing.

- Give students frequent practice, feedback, and support in applying these strategies independently.

- Encourage students to monitor their comprehension and adjust their strategy as necessary.

Identification of readers with unfinished learning is crucial, and evidence-based instruction should be employed to address their challenges. Interventions should be intensive, systematic, and regularly monitored to ensure students are making progress and improving their reading abilities (Institute of Education Sciences, 2008).

The IES Practice Guide can be accessed here.

Assessment and monitoring progress

To provide the necessary interventions for adolescent readers, schools must implement a robust Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) framework that offers multiple layers of support, grounded in evidence-based practices such as screening tools, diagnostic assessments, progress monitoring, and data-driven decision-making protocols—involving all stakeholders within the school community.

According to the American Institutes for Research (AIR), effective MTSS implementation in secondary schools centers on these essential components, with a particular emphasis on assessment and progress monitoring (AIR, 2020):

- Establish a Universal Screening Assessment for grades 6-12 and administer 3x a year to identify students who may require additional academic, behavioral, or socio-emotional support.

- Once at-risk students are identified, schools should utilize targeted diagnostic tools to pinpoint specific skill deficits, which can then be addressed systematically and explicitly through a tiered intervention approach.

- Students identified as requiring Tier 2 intervention should receive a standardized, evidence-based program targeting skill gaps within a small-group setting. Implement Tier 3 interventions for students requiring more intensive support which, according to AIR, involve data-based individualization (DBI).

- Establish a system for progress monitoring to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. AIR recommends that students receiving Tier 2 interventions should be progress monitored monthly, while those in Tier 3 should be monitored weekly.

Assessment and progress monitoring is the mechanism for forward movement for students. By taking time to evaluate skills every few weeks, it’s possible for students to move on from skills they’ve mastered and continue to fill gaps for those they still need.

Create a roadmap for success for your teen students

Many adolescents enter classrooms angry and defeated, exhausted by years of ineffective intervention. With structured literacy instruction grounded in the science of reading, students can grow and experience the confidence and joy that comes with mastery of foundational reading skills.

Unfortunately, too many lose access to consistent support as they move into high school—a reality for struggling readers across the country. Without continued intervention, progress stalls and students fall further behind. NAEP data confirms the urgency: only 37% of twelfth graders read at or above proficiency.

We have the knowledge and tools to change this trajectory. Now we must act.

Expert Biography

Jeanne Schopf, M.Ed., NBCT, C-SLDI, and Certified Explicit Instruction Trainer of Trainers, is a motivational keynote speaker and literacy expert with over 30 years of experience in K–12 education. As a Literacy Coach, Reading Specialist, and Certified Dyslexia Interventionist, she transforms learning experiences for students and educators while leading state and national literacy efforts.

A Certified John Maxwell speaker, trainer, and coach, Jeanne delivers research-based professional development grounded in Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) and the Science of Reading, equipping educators with actionable strategies for literacy instruction and intervention.

Jeanne founded Pathways Towards Literacy, a consulting company that supports school transformation through the implementation of the Science of Reading. She serves as an Independent Contractor for The Reading League, CORE Learning, An EdTech Company, and Transformative Reading Teacher Group.

Her mission is to help educators establish pathways towards literacy, ensuring all students access high-quality reading instruction.

Sources

- American Institutes for Research. (2020). MTSS training modules: Essential components of MTSS. Southeast Comprehensive Center. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/SECC_MTSS_Training.pdf

- Hernandez, D. J. (2011). Double jeopardy: How third-grade reading skills and poverty influence high school graduation. The Annie E. Casey Foundation.

- Institute of Education Sciences. (2008). Improving adolescent literacy: Effective classroom and intervention practices. U.S. Department of Education.

- Lyon, R. G. (2001). The research we need to guide our efforts to ensure that all children can read. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). The Nation’s Report Card: 2024 Reading Assessment. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov

- National Institute for Literacy. (2008). The state of adult literacy in America: A national perspective. U.S. Department of Education.

- U.S. Department of Education. (2007). The condition of education 2007 (NCES 2007-064). National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2007/2007064.pdf

- Vaughn, S., & Fletcher, J. M. (2012). Response to intervention with secondary school students. In P. A. McCardle & V. Chhabra (Eds.), The voice of evidence in reading research (pp. 319-335). Brookes Publishing.